We made quite a few predictions in the last year as the digital SAT made its debut, both about the changes to the test itself and also about how students would react to those changes. Here we are, a year and, for us, a thousand or so students later. So, what did we get right and what did we miss? And what can students just starting their SAT prep journeys learn from the experiences of the first crop of US students to test?

Prediction One: Students will be tempted by the shorter, digital SAT.

This one was 100% true. The College Board was super effective in its online marketing campaign: Essentially every student came in the door already knowing that the digital SAT is an hour shorter than the ACT. That fact certainly swayed their thinking, and not always for the better. Perhaps more than any year in recent memory, students this year switched from the SAT to the ACT or the ACT to the SAT – so many, in fact, that we blogged about it. Perhaps it was the college board’s aggressive marketing campaign, perhaps it was the fact that one test was digital and the other paper, but whatever the reason, students have been wondering about the road not taken. Let that be a lesson to students new to the process: taking time early on to determine which test is more aligned with your skills – and not simply more convenient – can save you time and indecision later!

Verdict: Absolutely True

Prediction Two: Vocabulary will be more heavily emphasized on the digital SAT.

We knew last year that sentence completion questions, for which students need to supply a vocabulary word into a blank in a short passage, were making a comeback on the SAT, but we weren’t sure the extent to which that vocabulary would permeate (as the SAT would say) the rest of the test. Of course, the SAT has always featured more challenging vocabulary and a generally higher level of diction than the ACT, and that remains true of the digital test. So the real question is, “Does the new SAT challenge students’ vocabularies more than did the previous iteration?” And the answer is, “Not really.” As it turns out, most of the challenge in the new SAT sentence completions is correctly parsing the context of the passage itself and not in identifying abstruse vocabulary from the answer choices. Of course, that context is itself written at a college reading level, so students whose vocabularies aren’t as expansive will likely still have an easier time reading – and understanding – passages on the ACT than those on the SAT.

Verdict: Somewhat True

Prediction: Shorter reading passages aren’t necessarily easier reading passages.

I don’t think a single student all year has lamented the loss of the “long” (80-90 lines) passages of the paper SAT. However, they haven’t all been happy about the newer passages, either. Specifically, we predicted that the new Information and Ideas section was going to prove difficult, and it certainly has. These questions require more from students than simply reading a short passage. Testers need to understand the structure of the arguments being made, distinguish evidence from supposition, and – in some cases – make a logical deduction of their own based on what they’ve read. Not all students have been comfortable making the transition from longer passages testing recall and understanding of main ideas to shorter passages that require more close reading and analysis of argumentation. Students struggling with those aspects of the test might be well served by checking out the ACT, which retains the legacy longer passages with multiple questions.

That also brings us to another prediction we made: the cognitive load of the new SAT would rise since each question now has its own short passage rather than fewer longer passages with multiple questions. That’s also manifested as a very real struggle for students, who’ve reported that their brains are just “too full” by the middle of that second reading module. Well prepared students, however, understand that they can answer the questions in any order they like! Many have found breaking up those difficult argumentation questions with some “easier” grammar or transition questions to be one successful way to not be overwhelmed by what can feel like a barrage of shorter passages.

Verdict: True

Prediction: Desmos is a game-changer.

This one is so true it’s almost unfair to students who don’t have experience with Desmos. Not only can students use the bundled graphing calculator to find solutions to problems they don’t know how to set up algebraically, but they can also wisely use it to solve other problems they know how to do, but more quickly and easily. Students who haven’t really engaged with Desmos in school are encouraged to start right now – the SAT has acknowledged that our math students are living in a digital age even if their math classes have not, and knowing when and how to use your digital tools can be as important as knowing the algebra! One caveat here, though: Desmos is tremendously effective in helping students turn poor or middling math scores into good scores. Desmos, however, is not going to be nearly as helpful turning really good scores into truly exceptional ones – for that, students will absolutely need to be comfortable with all the algebra.

Verdict: True

Prediction: A lack of resources will make it difficult for dedicated students to fully prepare for the digital SAT.

We’re happy to be wrong about this one. The College Board has done a good job this year of releasing practice materials via BlueBook, their online testing tool. Students currently have access to eight fully adaptive practice tests, which is as many as most will need. College Board also hosts an Educator Question Datatabase which features hundreds of additional questions in the current format that students can use for valuable additional practice.

Verdict: False

Prediction: Sparse score reports and lack of feedback will make it more difficult for students to prepare for a retest.

For us as tutors and for the students who choose to retake the test, this one really hurts: students no longer receive any meaningful feedback on their test day other than the overall section scores. Gone are the days when students could understand the type of questions they missed on the last round or even order a copy of the released test from the College Board. The digital SAT score report doesn’t even tell students how many questions they’ve gotten right or wrong, let alone what kind of questions those were! That’s proved especially challenging to two groups of students at opposite ends of the spectrum: students for whom testing doesn’t come easily and students looking for elite 1500+ scores. While being very different learners, those students usually test multiple times over the course of the year and – in the past – would heavily rely on detailed score reports to guide their long-term work. It’s important for all students, but especially those cohorts, to prepare for the uncertainty that’ll be coming their way by trying to themselves take as much feedback out of the test as possible. Be sure to write a note to yourself or your tutor with a brain dump to memorialize the day while the details are fresh so you can reopen it when scores are returned to try to help yourself understand what really happened and put yourself in the best position moving forward.

Verdict: Very unfortunately true

Prediction: The ACT will respond quickly with a digital test of its own.

This one is a little more complicated. The ACT is in the midst of transitioning to the “Enhanced ACT”, which debuted in April 2025 and becomes the only version of the test in September, when the ACT will make it available to students both digitally and in paper form. And, as expected, it’s also been trimmed to a snappier two hours to compete with the digital SAT. The ACT’s giving students a choice between a paper test and a digital test is great in theory, but thus far that choice has been only nominal. Unlike the digital SAT, which students can take on their own devices, the digital ACT must be taken on school managed devices, a proposition that not many test centers have embraced. For example, two months before the first digital test in April, the closest available seat to DC was actually in Pennsylvania. Unfortunately, we don’t anticipate schools to change until the ACT changes its policy on student-owned devices. The silver lining here is that the digital ACT, unlike the digital SAT, is a static test. That means students face exactly the same questions and format on a screen or on paper. And there’s no Desmos integration on the ACT, so there’s really no real reason for students to even want to take a digital ACT this year. Yes, it’s a new, “enhanced” ACT, but for most kids it’s still going to be a paper ACT.

Verdict: It’s complicated

We’ll be opining on the upcoming changes to the ACT this year as it rolls out and look forward to checking back in next year to see how we did! Until then, we’ll be busy adding to what we already know about the new SAT and learning as much as we can about the latest updates on the upcoming digital ACT. Please reach out to us if we can be of help to you or your family as you try to do the same.

Goodbye, Scantron sheets and #2 pencils. Hello, test-taking tablets, adaptive testing, and graphing calculators. After nearly a century as a paper-and-pencil test, the SAT went digital in March 2024. These changes make the digital SAT significantly different from the paper SAT — not just in format, but also in how questions are delivered, scored, and how much time students spend on each question.

What are the main differences between the paper and digital SAT?

Headline-grabbing changes include testing on a computer, different tests for different students, and the most celebrated of changes – its shorter length. Thank you! More subtle but no less significant alterations include new test-taking tools that are embedded in the test, changes in question types, and a reduction in transparency. In short, there are a lot of changes. We’ll walk through the changes, explain what differences (if any) they make, and consider what students can do to be prepared. Let’s dig into the details.

The traditional paper-and-pencil SAT consists of four separate sections:

- Reading

- Writing

- Non-calculator math

- Calculator math.

This model will be replaced with a streamlined dSAT (digital SAT) with

- Two modules of mixed reading and writing questions

- Two modules of math.

The second module will test similar content to content in the first module but will be purposefully easier or harder than the first. This is an important difference that we further explore below.

How long is the digital SAT?

First, let’s talk about the difference in length. The current paper SAT is considerably longer than any test students take in school, and this has long been an issue for students who struggle with sustained attention or stamina. It is also a logistical hassle for school-based administrations of the SAT, because three hours of content extends to a four-hour test-day experience. For students with an extra time accommodation, the total time is nearly six hours.

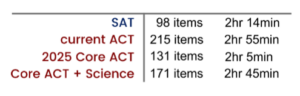

The dSAT will be markedly shorter; it is a 2-hour and 14-minute test – and because College Board is doing away with pretest questions and the experimental section, the total time remains close to a 2-hour 30-minute testing experience.

How did they cut so much time from the digital SAT?

It’s shortened mostly by asking fewer questions. Although the paper SAT contains 96 reading and writing and 58 math questions, the dSAT shrinks that to 54 reading and writing questions and 44 math questions. Notably, the end result is that the dSAT actually increases the amount of time per question.

You may wonder how on earth a shorter test with fewer questions can accurately arrive at scores in the same way as the paper SAT. In short, it doesn’t. It arrives at accurate scores with an adaptive, not a static, test. On the paper SAT, students answer the same questions, and scoring is straightforward — based simply on the number of answers that are right or wrong. On the dSAT, however, different students see different versions of the test, and some questions matter more than others.

What is computer adaptive scoring?

On the first Reading and Writing module, students will see a mix of easy, medium, and hard questions. Students who perform well in that first module will have a second verbal module that is primarily comprised of harder questions; students who haven’t performed as well will see an easier second verbal module with mostly easy and medium questions. By giving each student questions that are targeted to their ability, the test can more quickly pinpoint an accurate score. The math modules employ the same process.

Additionally, not all questions are created equal. Their value is based on several factors, including the degree of difficulty and the extent to which it’s possible for a student to guess the right answer. What does that mean for students? Simply put, getting an easy question wrong hurts more than getting a hard one wrong, while getting a hard one right helps more than getting an easy one right.

How does the SAT software work?

The digital SAT’s testing software introduces in-test tools that mimic the experience of taking a paper test. Students can highlight text, mark questions to return to later, and track the remaining time with an embedded clock. (No more craning of necks is needed to see an inconveniently placed wall clock.) Perhaps the most important software feature is the built-in Desmos graphing calculator, a sophisticated math tool that can be used to solve a wide range of arithmetic and algebraic questions. Students may also use their personal calculators, but they would do well to practice with Desmos and explore how much it can help. (It is no exaggeration to describe it as a “game changer.”)

Although the markedly different online tools and the absence of a non-calculator math section have caught a lot of attention, it is the content changes that students, parents, and educators would do well to understand. There will be winners and losers. The math content, with a familiar mix of algebra, geometry, trigonometry and precalculus, presented in both multiple-choice and student produced response (aka “grid in”) formats, has not changed significantly. However, the content and question types on the Reading and Writing section have.

How are the Reading and Writing sections different on the digital SAT?

To start, gone are long reading passages. Students will not see a wall of words to read before tackling questions but instead will see a few lines or a few sentences of text. For students, that seems like an obvious win.

College Board surely had several reasons for making this change, but one stands out: on the paper SAT, students simply were not reading the passages. Instead, many were reading the questions and then searching through the text for answers.

The new dSAT format presents students with only a paragraph or so at a time, but bite-size passages still add up to a heap of words. According to College Board, the Reading and Writing section of the digital test features 25-150 words per stimulus text. The paper SAT averages out to about 52 words of passage text per question across the Reading and Writing sections, so the actual total reading demand is similar. Also, shorter passages are not necessarily good news for everyone. Students who struggle with shifting their attention may find it easier to handle a long passage with multiple questions attached than a series of 54 brief single-question passages in a row.

New challenges Presented by the dSAT

The Reading and Writing modules of the dSAT only test a handful of skills, including vocabulary, grammar, the effective use of transitions, and the ability to read closely and make logical deductions about what you’ve read, all of which should please old-school English teachers. This is in some ways similar to the paper SAT, but in some ways not. The current paper SAT that launched in 2016 was in many ways a response to the ACT, which for a while eclipsed the SAT as the dominant college admissions test in America. Ostensibly designed to align with the Common Core, the 2016 SAT also aligned more closely with the ACT by jettisoning the last of its discrete vocabulary questions and focusing more heavily on punctuation than on the esoteric nerdy grammar that populated earlier versions of the SAT. Those changes persist. As in the ACT’s English section, the Writing questions on the digital SAT remain rooted in punctuation, with even the most challenging questions very much rule driven.

Conversely, vocabulary seems to be sneaking back into the test. In 2016, College Board president David Coleman announced that the SAT was getting rid of “SAT words,” and it mostly did. But vocabulary didn’t completely disappear from the paper SAT; the test just got more subtle about it. In place of the pre-2016 question types of antonyms, analogies, and sentence completions, vocabulary challenges were embedded into the aforementioned long(ish) reading passages. In the dSAT, vocab is back more explicitly, appearing in questions that look a lot like resurrected sentence completions. Although there may not be a rush to brush off boxes of vocabulary cards (as the words tested are not particularly obscure), the dSAT will reward students with strong vocabularies.

Information and Ideas on the digital SAT

Finally, the most significant content change on the Reading and Writing is likely the introduction of “Information and Ideas” questions, which ask students to draw inferences, strengthen or weaken arguments, or otherwise demonstrate their analytical skills. Essentially, these questions are similar to the logical reasoning questions found on the LSAT, GMAT, and GRE, and the hardest of them are a significant challenge. Unlike the old “Where’s Waldo” type questions, these require both close reading and careful logical thinking.

With all of these changes, what is staying the same?

Students who take the dSAT are still required to test at approved testing locations, generally local schools. The scoring remains on a 1600 scale: 200-800 for Reading and Writing, 200-800 for Math. Unlike in previous overhauls, College Board will not release a new concordance table to “convert” scores from one test to another as College Board has offered assurances that the two forms of the test align closely enough that none is needed. Special accommodations that existed for the paper SAT, including ezra time, will remain for the dSAT.

Accommodations such as audio versions of text will be even easier to deliver on the dSAT. Significantly, however, students who are hoping to take the test on paper, knowing or believing that they process material better on paper than on a computer screen, are out of luck. College Board has stated that a paper version of the test will be made available only to students whose disability creates an “inability to use a computer.”

Practice and Feedback from dSAT Testing are important

Finally, one last point for students to consider is this: feedback, not just practice, matters. Unlike on the paper SAT, students will not be able to see what questions they got wrong on the dSAT. The paper SAT offered a Question & Answer Service (QAS) for certain test dates, which provided students with access to the actual questions they saw on their test so that they could better analyze their performance. That service does not exist for the dSAT, so students will not be able to see what they missed and will not be able to determine why they answered incorrectly. Hard question? Foolish mistake? Who knows? That lack of transparency may be the biggest hurdle created by the dSAT.

Focus is key for success

Additionally, at least for our students who took the digital version of the PSAT, test-takers were somewhat staggered with their start times, breaks, and stop times, meaning that other students were coming and going during the test. Does that really matter? Yes. In one seminal study by the Department of Defense, 2.8-second interruptions (on a computer!) DOUBLED errors by disrupting attention — and, what’s worse, the test-takers didn’t even realize it. This means that taking practice tests in a setting that imitates the real thing is especially important for the dSAT. Taking tests at home is not the same!

The good news is that, as with every other version of the SAT (and some of us here at PrepMatters are now on our fifth version), students can get better with practice. However, the nature of the practice matters. To solve problems, it is important to understand what caused the problem in the first place – and working through practice test results and other missed questions with a trusted professional makes all the difference.

SAT Prep Services from PrepMatters

PrepMatters has provided test preparation services for over 25 years in the Washington, DC and greater DMV community. Our SAT tutors specialize in helping kids prepare in a way that sets them up to succeed on test day and, in addition, to develop positive study and academic habits. We would welcome the opportunity to help your student.

Frequently Asked Questions

Both exams test students’ reading, math and grammar skills, but, in general, the ACT subjects students to more time pressure as they answer more straightforward questions. By contrast, the SAT is designed for students not to run out of time, but the questions are more abstract and nuanced (a student would say “trickier”) than those found on the ACT.

While both tests have a Math section, Math makes up one half of an SAT score, but only one third of an ACT score. That being said, the SAT math content features less precalculus and students are equipped with the built-in Desmos graphing calculator, which is not available on the ACT. When in doubt, students are always advised to take official practice tests to see which better suits their strengths.

You clearly cannot write on your computer screen, but the digital SAT does provide tools to highlight and even add text comments the passage, strike eliminated answer choices, and mark questions for review later.

The digital SAT is 2 hours and 14 minutes long. That’s substantially shorter than either the traditional 3-hour paper SAT or ACT, a feat achieved by the new adaptive nature of the digital test.

The digital SAT is shorter and offers built-in tools, but it’s not necessarily easier. The adaptive format gives students questions tailored to their performance, but this doesn’t mean the test is less rigorous. Instead, it aims to more efficiently assess each student’s abilities.

Renowned French scientist Louis Pasteur observed that “Fortune favors the prepared mind.” There’s not only a what and a how to being prepared but also a when. Just when should students begin test preparation for the SAT? In his work with viruses, Pasteur discovered that the correct dose at the right time, enough to tax but not overwhelm, with enough time to build resistance and immunity, was the key to preparing the body against dangerous viruses.

While standardized tests may not technically be virulent, the same sound logic applies to preparing for college admissions tests. Too strong a dose can be noxious, too little inefficacious. Start too early and the effects wear off, start too late and there’s not enough time for the benefits to take hold. When matters. The rest of this post will discuss all the important details of when to start SAT test preparation.

Deciding When to Start Preparing for the SAT Test

So, when is the right time to start SAT test prep? Let’s start with the end in mind: college applications. For early admission deadlines, you’ll need excellent scores by October of your senior year; for regular deadlines, by December of senior year. Intuitively, you need scores earlier for early deadlines, so you have them in hand by the time you apply to college.

For other reasons, you may want good scores earlier than that. Ideally, you can be finished with testing by the middle or end of junior year. Given recent changes in testing policies, SAT scores are again an increasingly important, if not essential, part of applying to highly selective colleges. Scores are also important in determining scholarships and merit aid shopping over spring break, broadly framing both admissions chances and what you might pay.

Another reason to prep for the SAT before senior year is that the start of senior year is a Very. Busy. Time. In addition to enjoying being a newly minted senior, you’ll be working on college applications and essays, while still keeping your grades up. It’s a lot. You certainly can retake the SAT in senior year, but ideally you’ll have test prep behind you before senior year.

Okay, so when should you start? For most students, the summer after sophomore year is the right time to begin prep. One, you will have learned most of the math you’ll need. Two, you will have a few months to get some practice under your belt before your junior year PSAT, with plenty of opportunities to take the SAT before the end-of-junior-year crunch of final exams and APs (if your school offers them). Three, everyone else is doing it. Honestly, camaraderie can help – you’re not in this alone!

But don’t freak out if you don’t start test preparation until the beginning or midway through your junior year. Lots of activities and life can happen over the summer, or maybe your fall calendar is just too full. I have been working with high school students since 1993; I get it. Almost always, the problem is not with students starting too late but students (or more likely their parents!) wanting to prepare too early. Seriously.

Is 9th or 10th Grade TOO early to start SAT prep?

In my experience, people look to start SAT prep early for one of two reasons: to fill in significant learning gaps or to keep the stress low. The first I can (mostly) get behind, but please look for math tutoring or reading help – not test prep. The second paradoxically usually backfires. Here’s why:

Starting too early can actually increase stress because:

- You will face a lot of new, yet-to-be-learned material, which causes stress and an early loss of confidence.

- You may lay the foundation for a stressful environment surrounding test preparation.

Now I know you may have a cousin whose kid started prep in 9th grade and did great—but they likely did well despite starting early, not because of starting early.

CAVEAT for Future Athletes: Students who are recruited athletes may face pressure to share scores with coaches at the start of junior year, in which case prepping a little early may make sense. But, again, only a little early is best, as in part way through sophomore year.

Optimal Time Investment for Test Prep

Okay, got it: start SAT prep after sophomore year. How much then? Generally, students do well to allot three to six months for test prep, depending on what you know and the schools on your college list. Target scores should be based on the average scores (25th-75th percentile) of colleges on your tentative list, based on your academic profile. When you know the SAT scores for those colleges and where you are currently scoring, you can determine how big of a gap you have to close and thus how much work is needed. Cramming in a few weeks is a dubious approach, but a three-year plan for test prep is not recommended either.

How many months do you need to study for the SAT?

Yes. Students do well to allot three to six months for SAT test preparation. It is important to remember that you are learning and practicing skills that can also be reinforced each day in school. We have done prep for 25+ years, and we have seen our staff work with students to achieve terrific results within this window. Trust us, we too want you to succeed!

Prioritizing Grades and Test Prep

Grades are the most essential criterion for college admissions, but good test prep can help raise your scores to a level as high or higher than your grades. Additionally, test prep can improve your math, grammar, and performance under the pressure of timed tests. Nevertheless, you do not want to work hard to raise scores if you lower your grades. Grades first, test prep second.

How Do You Know When You’re Ready for the SAT?

At a basic level, you’ll be ready to ace a test like the SAT when you have the right knowledge, skills, and a brain state to allow you to perform your best (or close to it) under test-day pressure. Knowledge is relatively straightforward: you must know math, grammar, punctuation, test structure, and test-taking strategies.

However, knowledge can be fleeting if not practiced regularly. Sadly, most students forget 90% of what they learn in school within three months, which may explain why so many A students are initially stunned by their first scores. Three to six months allows for interleaving and enough time to learn or relearn at a pace that allows things to stick.

Essential Components of Test Readiness – Building Critical Skills

Starting test prep at the right time is also important for building skills. Sure, you aced every math quiz in the last two years, but do you know what formula or tool to apply and when? Students often take quizzes with exponent, percentage, or quadratic problems. Usually, all three types of problems are not presented at once. When school tests are topic specific, it is easier to know what tool to use and when. It’s a different experience on the SAT – knowing what the question is asking and what skill to apply often is what is being tested. The SAT are akin to final exams on three years of math, all mixed up under time pressure. Knowing what the first step is matters just as much as executing the steps.

Strategy matters too. Performing well is not so much following a script as knowing how to dance – or improvise. The SAT reward students who mix and match approaches, who can be creative under pressure, figure things out on the fly, and find efficient ways to solve problems, including how to use “tricks strategically ” (AKA using 8th-grade math tools to answer 11th-grade math). As students move on to higher math, they often apply the most powerful tool in their toolboxes rather than the most effective one: a chainsaw may be a powerful tool, but sometimes a bread knife can get the job done just fine. Effective test prep helps students broaden the tools they are comfortable using, teaches them how to deftly apply them, and allows enough time to be practiced before the actual test.

Essential Components of Test Readiness – Motivation and Stress Tolerance

Ok, but should it be three months or six? That is a good question. Here’s a sideways answer. It depends. On your student. If great scores were only a matter of knowledge and skills, you likely wouldn’t be reading this blog. Focus matters. Motivation matters. Thinking well under pressure matters. Brains, like students, can be complicated.

Let’s take a field trip into some brain science.

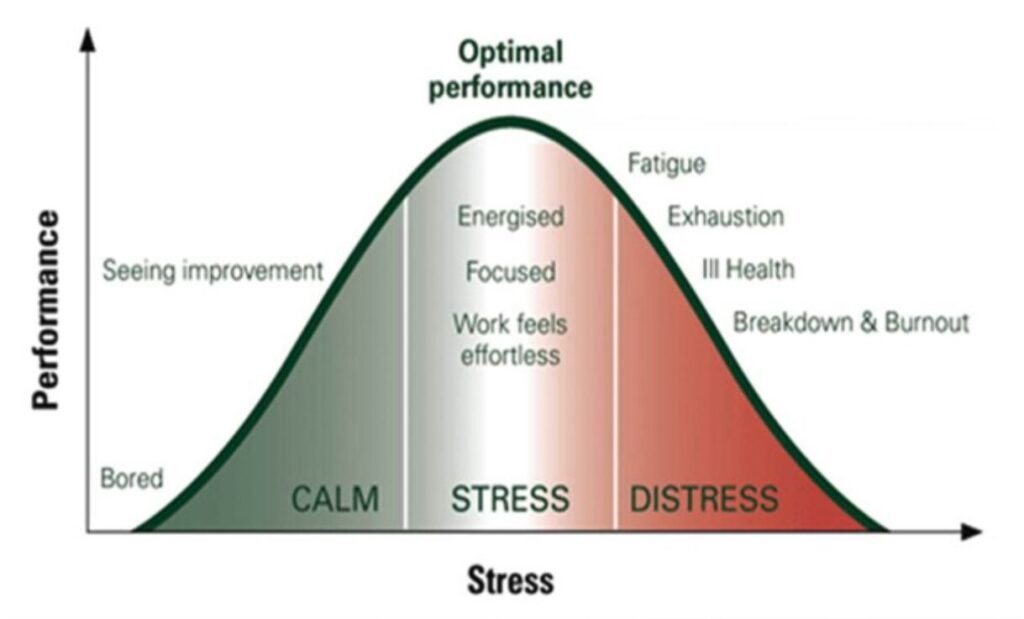

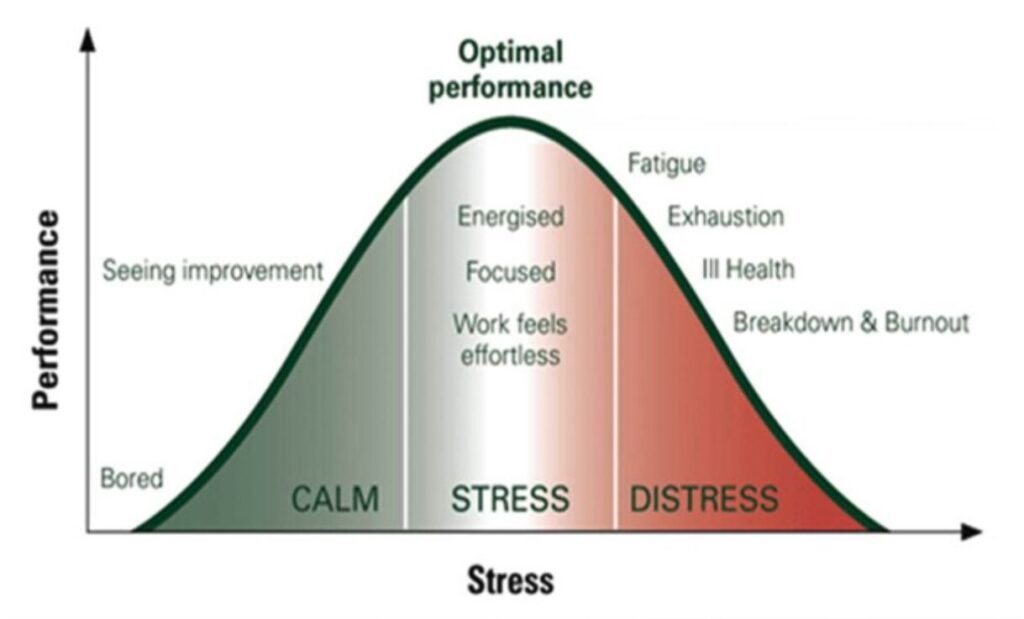

The Yerkes-Dodson Law describes how excitement and stress (in the scientific parlance, physiological arousal) affect performance.

Without enough stress, engagement is meh. Too much stress blows up performance, as overly stressed brains simply don’t learn or perform well. Importantly, for every person in every activity, there is a zone of optimal arousal, what neuroscientist Amy Arnsten describes as the “Goldilocks zone”: excited just enough (motivated) but not overly stressed (test anxiety).

Some students perform better with less pressure. Others with more. The kicker can be a parent who imagines their child feels what they feel, especially if a parent feels urgency when their kid doesn’t. To maximize the ROI of parent money and student time and energy, when matters, for starting at the right time will impact the brain state students are in both through the prep process and on test day.

How can you know what the right place is for your son or daughter? You can’t. But together you can. When making a plan for test prep, it’s really important to make it with them not for them. Why? Well, two reasons. One, the only person who knows what they are feeling is that person – where a person falls on the Yerkes-Dodson curve is subjective. Two, motivation and anxiety are both HIGHLY connected to a sense of control. A low sense of control undermines motivation and supercharges anxiety. You’ll get both better effort and outcomes when you consult with rather than manage your student and their test prep. But that’s not always easy.

Benefits of Professional Test Prep Tutors When Preparing for the SAT

Professional tutors can help you and your student craft the right test prep plan for them – their personal Goldilocks approach.

Since tutors will help students stay on the task to execute their test prep plan, it makes sense to have those same tutors work with families to design the test prep plan. As kids navigate test prep and the college process, it helps to have parents who are steady, supportive, and sane. Tutors can take the stress load off of parents, who often try to take on the dual role of parent and test-prep coach, which leads to increased stress for all involved. For more than 25 years, we’ve had the good fortune to help thousands of families prepare for and succeed on the SAT.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Should I Prioritize Grades over Test Prep?

Why else should students start SAT prep later? Grades are the most essential criterion for college admissions. Full stop. The plan is for good test prep to help raise your scores to be as high as or higher than your grades, not to have them to meet in the middle: you do not want to work hard to raise scores if you lower your grades in the process. Grades first, test prep second.

Can you prepare for the SAT in a month?

Yes, it’s possible to prepare for the SAT in a month, but it takes a focused and strategic approach. Prioritize full-length practice tests, target your weakest areas with high-impact review, and consider using a tutor or test prep program to stay on track and maximize your results in a short time.

Is it better to start SAT prep in sophomore or junior year?

For most students, starting prep in the summer after sophomore year is ideal. This timing allows enough room to build knowledge, practice effectively and take multiple test attempts if needed, without the added pressures of junior and senior year activities.

How many hours per week should I study for the SAT?

On average, one to three hours per week (especially once full practice test commence) over 3-6 months is recommended for effective test preparation. Focused prep trumps lots of prep, especially for already busy students. However, the exact amount varies depending on your starting point and target score. More intensive sessions may be needed for students with shorter prep periods.

The Right Time for SAT Prep

Timing is crucial when preparing for the SAT. Starting at the right moment—typically the summer after sophomore year—gives students the time to build knowledge and confidence without added senior year pressures. However, starting later can still lead to success with a focused approach.

Please contact our team to schedule a time to learn how working with the right tutor can help your son or daughter succeed.

We get kids. We get tests. We help kids get tests. We’d love to help yours get theirs.

What is a typical SAT test time start?

The SAT typically starts between 8:00 a.m. and 9:00 a.m. local time. Students are usually asked to arrive early to check in, find their seats, and receive instructions. Generally, students should plan to arrive no later than 7:45 a.m., but always check your admission ticket.

How often per month should I take SAT practice tests?

Taking one full-length SAT practice test per month is a solid strategy for most students. It allows time to review mistakes, adjust study plans, and build endurance without causing burnout. As the test date approaches, you may increase frequency to one practice test every 2–3 weeks if time allows.

That’s a common enough refrain this time of year for any junior not yet fortunate enough to be done with their standardized testing. But this year that refrain has grown into a chorus because of the recent debut of the digital SAT. Students who chose the SAT because it’s shorter and digital might be disappointed to find it harder than they suspected. And those who felt the ACT was the better option are likely thinking the SAT looks shorter than ever. Students should try to put their results into perspective, however, and not overreact to one bad score. Here are a few questions you should ask yourself before you decide to make a change.

Bad Match or Bad Day?

If you’ve only taken the test once and had a thoughtful reason for the test you chose, you should likely stick with it. Don’t confuse the feeling of needing to retest with the feeling of needing a new test. And, if you haven’t already, you should check out the entire blog we wrote on whether or not to retest, a decision that depends on a number of related factors.

- Could you have reasonably worked harder, given your current schedule, to prepare for the test?

- Did anything strange happen the day or week of the test that could explain lower than expected scores?

- Were you more anxious than you expected to be?

If your answers to any of those three questions are “Yes,” then you’ve got valid, rational reasons for why you didn’t reach your goal. Moreover, those reasons also give you prescriptions for the most helpful path forward: Didn’t work hard enough? Work harder. Crazy three days before the test? Plan better. Test administration snafu, sniffling student, or phone-call-taking proctor? Remember that even small interruptions can double error rates. More anxious than you thought? Take more practice tests. But if the answers to all of those questions are “No,” you may be ready to give that SAT or ACT that you passed over another look.

Deciding which test to take is an imperfect science, and even professional tutors can make mistakes about which test is “best” for a given student. We’ve seen students who were very close to their goals on the ACT, who just needed a little work on pace and time management. Well, that can be easier said than done… If you’re already working as fast as you can work and using all the strategies at your disposal to save time but you still consistently run short on all your practice tests and the real thing, you can definitely feel stuck. In the same way, we’ve also seen students who “need another 40 points” on a SAT section but just can’t get there. Maybe it’s math and they’re already using Desmos wisely, have reviewed all the material, but just can’t figure out those tricky ones at the end. We’ve also seen students whose reading scores have reached the ceiling of their reading skills: to make more progress they’d have to improve their reading skills (a long-term proposition), since they are already using the correct strategies for each question type and are making good decisions with the understanding of the passages they do have. If you identify with either of those vignettes, it’s likely worth your time to reexplore the SAT or ACT, respectively.

Some Good News

Whether that last result was the result of a bad day or a bad match, here’s a bit of good news: much of what you learned for the test you’ve already taken translates well to the test you haven’t. So don’t think of it as having “wasted” however many weeks of test preparation but rather as having gained skills that you can use in your new endeavor. That’s especially true for the grammar and math questions: both the SAT and ACT test essentially the same set of grammar rules and most of the same math skills. That means all those little hacks you learned, like picking numbers when you see variables in the answers or eliminating prepositional phrases to help in a subject-verb agreement question, will still help you! And while the reading sections differ greatly, they both prioritize close reading, finding evidence and understanding arguments, and they both reward logical thinking and answer elimination – skills you’ve definitely been practicing.

So don’t be afraid to dive right back in with a full practice test to establish a new “baseline” – you might be surprised where that lands. And if the thought of spending the time to take a full practice test seems like more of an investment than you want to make right now, then you should reconsider how much you want to switch tests!

With any luck, you’ll be closer to your goal than you thought you were and that alone will likely give you the boost you need to push through with the additional preparation you might need for your new test day. Or, it could be the case that a full practice test reminds you just how much you disliked that test to begin with. In that event, you can either decide to reassess your goals, or you can go back to the test you were working on without the niggling doubt that the grass is always greener, also a win.

Now Is The Time

It’s a surprise to no one that the ACT is following the SAT’s lead and unveiling a shorter, digital test of its own this fall. That means the clock is about to expire on the ACT as you know it. At the time of this writing, there are only three more opportunities to take the existing paper ACT: May, June and July. So if there are good reasons for you switch from the SAT to the ACT, you don’t have any time to waste and will want to discover them soon! Conversely, if you’re an ACT student having second thoughts, you’d be better served by exploring those now so that if you do decide to return to the ACT, you’re returning to the ACT you know rather than the ACT you don’t!

Most students won’t be served by “waiting” to try the new digital ACT in the fall. For one, that realistically leaves only two options: the September test and the October test. That’s not much runway to land the plane if you haven’t already done so. Additionally, the new ACT will come with all the vagaries that new tests invariably possess, such as a lack of realistic test prep materials and an uncertain “curve”. One important exception exists for some students, though. Since the new ACT will only average the English, math, and reading sections to form the composite score, ACT students for whom Science is the only chink in their armor might actually benefit from holding off until the new test. If that isn’t you, however, now is the time to act and we wish you the best!

And, if all of this advice has your head spinning with options that make you feel more anxious than excited, give us a call. While you may have taken the ACT or SAT more than once, you likely haven’t made choices about the ACT or SAT more than once. The good news is that we have. We’ve helped thousands of student and their parents make informed decisions that worked for them, and we’d gladly do the same with you.

As we noted in our last blog, the new SAT reading and math sections both place a greater demand than ever on working memory – the ability to hold information short-term to perform immediate tasks such as reading comprehension, problem solving, and reasoning. Standardized tests can’t help but burden students’ working memories: On a typical reading question, students need to read and hold in their minds the meaning of a paragraph or two while they think about the answer to a question they’ve also just read. But the SAT is a multiple-choice test, so they need to continue to think about that question while reading each of four often complicated answer choices while also referencing the content of the passage they still hopefully remember. On the math side of the test, interpreting the given information and deciding upon a solution strategy presents a working memory challenge before students even get to whatever complex algebra or geometry might be required to actually solve the problem.

Sounds like a lot, right? For many students it’s too much. One way for students to improve their scores is to employ tools, strategies and techniques to lower the cognitive load of the test and the concomitant working memory demands.

Do NOT use your brain as scratch paper!

The three core executive functions are working memory (the ability to “hold” things in your mind. Think “scratch paper’), cognitive flexibility, and inhibition (self-control). More advanced executive functions include planning, organizing, and decision-making, among others. We all have a finite amount, so we want to be strategic about how we use it. So, if we are using our brain (prefrontal cortex) for one task, we have fewer cognitive resources for others. This is why we WRITE things down. Use your mind for thinking. Let scratch paper be scratch paper, for the scratch paper will not swap with you and do the thinking!

SAT Math Tools: Your Brain, Your Pencil and Desmos

The switch from a paper-based test to a computer-based one was greeted with cheers by many digital native Gen Z students, but that change introduces another significant layer of complexity on the math test. Having the questions on a screen, but working on paper, places a cognitive demand of holding things in your mind while you get things on paper, as well as switching attention back and forth from your page to the screen.

Some students have responded by doing most everything possible on Desmos, the sophisticated fancy new embedded calculator in the digital SAT. And, that’s great…to a point. For many students, the SAT has been wonderfully Desmos-able, something College Board has noted. While, Desmos seems still as helpful as it ever was for turning a bad math score into a decent one, it’s not as helpful as students would like turning a good score into an elite one. College Board has always maintained that the SAT is not simply about memorizing facts and formulas but about knowing what tool to use and when. About this, at least, they are 100% correct.

Desmos is in essence a tool, but not one that can replace reasoning and problem-solving. The funkiest of math problems really require math reasoning. We’ve taken note of recent problems designed with “Desmos traps” that entice students to choose close but wrong answers, so that students may feel more confident that they have correct answers to questions when they don’t. For those problems, because the answers are not ones that students have reasoned their way to, students cannot know their answers are wrong.

Successful students, however, will use the right tool for the right job. They’ll use desmos for graphing and computation, but only in support of solutions they’re working out themselves the old-fashioned way – with pencil and paper.

SAT Reading Tools: Cueing, Highlighting and Elimination.

Returning to reading, even if the SAT reading questions were all easy (they aren’t), reading on a screen is not the same as reading on paper. Reading expert Maryanne Wolfe notes significant differences between digital reading and deep reading:

In describing the wonders of the “deep reading circuit” of the brain, Wolf bemoans the loss of literary cultural touchstones in many readers’ internal knowledge base, complex sentence structure, and cognitive patience, but she readily acknowledges the positive features of the digitally trained mind, like improved task switching.

Fortunately, the BlueBook app provides tools and presents passages and questions in ways that students can take advantage of in order to deepen their digital reading experiences.

In the days of the paper test, students would first need to deeply read a longer passage before even engaging with the questions. But the digital test is different: each question has its own short passage. The downside, of course, is the sheer number different passages to contend with. One way the SAT Reading section maintains its high cognitive load is that it never lets students do anything long enough to get comfortable: every 71 seconds they’re looking at a different passage (if they want to finish the test, that is!) One of the best ways to combat that is to read the question stem first. Are you looking to strengthen an argument? Weaken one? Provide a conclusion? Just as shopping with an actual list keeps you focused on the items you need and less apt to be swayed to buy ice cream, knowing what you’re looking for as you read makes it much easier to find, and it should also trigger a process for you. “Oh, it’s a structure/function question, I’ve seen those before and know what to do!” Even though the passages are always new, the questions are not, providing a touchstone of comfort and familiarity.

The testing tool also comes with a highlighter that works both on the questions and the passages (though, sadly, not the answer choices themselves.) That’s not to say students should make indiscriminate use of it: taking twice as long to read a passage that’s now pretty much completely highlighted is a waste of time. Successful students understand that “careless errors” or “stupid mistakes” are often simply mistakes of attention, and a highlighter is a great way to draw your attention to where it needs to be. Are you often fooled by verb agreement questions? Highlight that simple subject in the sentence. Do you sometimes fail to answer the right question, having gotten confused after reading all those answer choices? Highlight the 2 or 3 words in the question stem that are telling you what to do. Do you sometimes understand passages “backwards” having misunderstood something important? Highlighting transition words in the passage can help you follow the logical flow. In short, there are lots of ways to successfully use your highlighter, so try to find quick and easy solutions that bring your attention right to where you need it most.

While you unfortunately can’t highlight the answer choices, you do have a tool that can eliminate answer choices you think are wrong. And most students *never* use it. Here again, it’s all about moderation. You shouldn’t waste time striking answers for an easy question you’ve already found the answer to. But if you’re struggling on a complex paired reading passage or a quantitative evidence question with a confusing graph, it can be really helpful to visually eliminate an answer choice in which you’ve found a flaw. Those sorts of questions can present a sometimes overwhelming amount of information on the screen for you to process. So anything you can do to remove some clutter is helpful. And when you strike out that wrong answer choice, you’re also, in a sense, removing that clutter from your brain. That’s especially valuable to students with ADHD whose brains struggle to see the signal through the noise. They now have less to consider and the problem feels that much easier. The very act of eliminating that answer choice also just feels good, right? It’s a tangible sign that a student is making progress on a problem that otherwise might have you them staring and confused.

Distractions and Task Switching

Finally, all that the shorter questions and frequent task shifting that students profess to like may not actually be all that good for them. Distractions cause stress and errors. As Gloria Mark notes, there’s “a correlation between frequency of attention switching and stress. So the faster the attention switching occurs, [the higher their stress].” But why do those distractions cause errors? Anything that demands our attention creates an additional demand on our working memory. We can only hold so many tasks in our mind. Things get dropped. Now, where was I? Where is my phone? More so, a greater demand on any executive function (working memory, inhibition, cognitive flexibility) depletes cognitive resources for another demand. Oh, and importantly, error-monitoring is another executive function! As noted earlier, it is cognitively demanding to both do a task and assess oneself doing that task – catching one’s own error. For anyone prone to “stupid mistakes,” this is what is going on. For what it’s worth, it happens to all of us. It’s just that some people are more vulnerable than others; things like ADHD and anxiety increase the likelihood. And students may not even know it.

In a fascinating study, researchers found that brief interruptions of 2.8 seconds doubled error rates of subjects completing a task on a computer. ““So why did the error rate go up?” Altmann said. “The answer is that the participants had to shift their attention from one task to another. Even momentary interruptions can seem jarring when they occur during a process that takes considerable thought.”

These brief interruptions are part of life – phone notifications, texts, children, and spouses – all compete for our attention. But, standardized tests are purposefully administered in ways designed to minimize distractions. Cool! That is why they are proctored so formally. But, here’s what I experienced. On paper tests, I mostly have my head down. Taking the SAT on the computer, my head was literally up. Without intending to, I was more aware of other students and their computers. Of the room around me. Of the temperature in the room. Of that ceiling tile with a strange blob on the corner. Of the clock. It’s also worth noting that while students in the same room start the test at roughly the same time, they do not start at precisely the same time, as we all had our SAT timed on our own computer. With all these new distractions and the fact that my head was physically up in ways it has never been before (for someone who has taken the SAT countless times at this point), the timer on my screen feels different! And working memory is going to play an even larger role in this new SAT! So be ready! And remember on!

The Digital SAT has finally arrived! While I am kind of an analog guy, the SAT, like many things in our world, has adapted to our screen-based society. And while some lessons can be learned from the practice tests made available from College Board, there are different lessons to be learned from taking the actual test itself. So, what did we learn?

But, before we launch it to what we learned from taking the test, allow me to answer the question that may hang in the air: Wait, tutors take the SAT? Yep, my colleagues and I take the SAT and ACT for two primary reasons:

- We want to see for ourselves what the SAT is like and what the SAT experience is like. It’s also important to note that with the new digital SAT, College Board no longer releases a copy of the test that students take. Therefore, we cannot go over the questions with them, and it is difficult for students to both do the test and assess how they are doing. Doing two things at once imposes a really high cognitive load, so it helps us as tutors to take the test itself. Shooting hoops in a gym without the crowd does little to inform what the experience is like shooting a game winner as the clock winds down. While we read closely everything that College Board shares about the SAT and listen closely to what our students report, experience has taught us that we may not be getting the full picture. As President Reagan intoned, “Trust, but verify.”

- We take the SAT and ACT to appreciate the subjective experience of what it’s like to take a high-stakes, early morning test that creates anxiety for pretty much everyone, from proctors to students to middle-aged test prep geeks like me. Boots-on-the ground observation allows us to better advise students and, honestly, garners us a tad bit of street cred. You know, if you lived on a nerdy street in an academic neighborhood with rival gangs of Scholars and Geeks. And, yes, to answer your question: We are allowed to take the SAT. For better or for worse, there is no age limit to the SAT. To my amusement, taking the SAT is often the penalty paid by 20-somethings who lose their fantasy football leagues, which could also be your fate as a parent if you push your kid too much – be careful how much you hassle or harangue your student to put in more effort, lest you elicit an invitation to join them one Saturday morning!

So how does the new SAT feel to take? Many of the changes students profess to love about the new test don’t necessarily make the test easier or better for them. How so? Well, let’s start with what makes the SAT difficult. Well, not just the SAT, but today’s SAT. While parents may have memories of vocab cards and #2 pencils, the SAT that students experience students today is quite different, as is the experience of taking it. While students did veritable cartwheels at the announcement of changes on the new SAT that seemed to promise an easier SAT – shorter passages, no more “SAT words” vocabulary, Desmos (an embedded sophisticated graphing calculator), and nearly an hour less of testing time, on a computer no less! Shorter and easier? What’s not to love?!? Folks like me who have watched multiple iterations of “New SATs” (five and counting for me) reserved our judgment with more than a modicum of skepticism. Shorter can be measured several ways. Shorter may not mean easier. Easier is not about individual questions but the test as a whole. As with every change, something has to give.

Why the Digital SAT is Easier for Students

First, some good news. Technologically, College Board has its act together. Fears of crashing servers and seizing systems that haunted the dreams of students and critics never materialized. Thank heavens! While the first digital PSAT in October 2023 had widely reported hiccups, today’s SAT is pretty darned smooth. Good news for all. That being said, students should read (and parents should confirm) BlueBook Instructions. The few tech errors we see are usually PEBCAK errors – which is to say, avoidable.

And, as expected, a shorter SAT does, in fact, take less time. Surprise! The good news is that students are no longer taking a test that bridges lunch, especially a concern for students with extra time accommodations. At the SAT I took, there was some kind of proctoring issue that caused us to be 30 minutes behind other classrooms, but we were still out before noon. Sadly, College Board has not used the opportunity of a shorter testing time to create a later testing time – ignoring a small mountain of evidence and a recommendation by the American Academy of Pediatrics for later start times for teens.

Why the Digital SAT is Harder for Students

But, does shorter mean easier? Well, not so fast. Classically, the difficulty of standardized tests is predicated on two factors:

- Power – the absolutely difficulty of questions and,

- Speediness – how much stuff in how little time.

One of the things that caught our attention in early pronouncements (aka marketing efforts) by College Board was touting a shorter test format, increased time per question, and shorter bodies of text. Well, golly, shouldn’t that make it easier? Seems so, right? Except, the SAT is a standardized test. Normal distributions (aka bell curves) are the coin of the realm for test makers (fancy statisticians called psychometricians), so something has to make the test and certain questions difficult, at least for some test takers. To keep score parity from the old SAT to the new SAT, lower speediness means greater power. On math, that tends to mean either more advanced or “trickier” problems. On reading, increased power is found in harder vocabulary and syntactic complexity (read: complex, wordy sentences). Is that what happened? (Spoiler alert: That is what happened.)

The new SAT Reading section: Is shorter better?

Arguably the thing I hear most from students who voice a preference for the SAT over the ACT is that they just “hate” the long reading passages. So, shorter has to be better, right? There are many reasons that many students dislike and struggle with reading long(ish) texts, and it’s not just TikTok. Kids (and adults) don’t read the same as in years past. To begin with, most of my students report that they have never had physical textbooks. There are many reasons why, most of which are likely financial. Instead, they get texts provided in pieces, usually digital. And, there are really significant differences between how brains process texts on screens versus in print. Because of our changing habits, people today simply have shorter attention spans. In her 2023 ground-breaking book Attention, researcher Gloria Mark shines light on our dwindling attention. “Back in 2004, we found the average attention span on any screen to be two and a half minutes on average. Throughout the years it became shorter. So around 2012 we found it to be 75 seconds….This is an average. And then in the last five, six years, we found it to average about 47 seconds…The median is 40 seconds. And what this means is that half of all the measurements that we found were 40 seconds or less of people’s attention spans.”

Previous versions of the SAT had reading passages that were typically 60-90 lines of text, which most students read in three to four minutes – if they read the text at all!! At a conference I attended in the run-up to the digital SAT, College Board shared that one reason for the changes from long passages to short ones was that they found far too many students were simply not reading the passages. Much like people skim webpages for what they are looking for, students were doing the same. And, it turns out that students were not doing well on reading comprehension questions when they did not in fact read passages to comprehend them. Who knew?!? In response, College Board made the passages (if you can call then that) shorter, typically 8-9 lines of text.

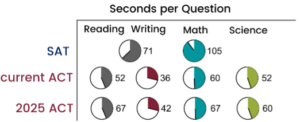

Ok, sure, but still shorter is easier, right? Well, maybe. To begin with, while the length of passages has shrunk, the average number of words per question remains robust. In promoting the new SAT, College Board strained to emphasize the greater time per question. Fair. On the ACT, a typical reading passage is 80-90 lines long. For many students, that feels like a lot. With ten questions per passage, that’s 8-9 lines per reading question, roughly 80 words per question. On English (mostly punctuation and transitions), about 20 words per question. And, the SAT? The reading and English are combined with roughly 105 words per question. And, while the SAT does give more time per question than the ACT (1.23 min vs. 0.7 minutes per question), the words per minute is flipped: 85 words per minute on the SAT while the ACT is 88 words per minute on reading 35 words per minute on English, a blended rate 41 words per minute.

Of course, all questions and all words are not equally difficult. While the SAT famously jettisoned “SAT words” and no longer discretely tests difficult vocabulary with analogies and antonyms, it does discreetly test vocabulary, with words that many students don’t know obscuring the meaning of the sentences themselves. The length of sentences is only one measure of their difficulty. In fact, many types of lexile scores exist to rate the reading level of texts for this very reason: Vocabulary and sentence complexity both matter!

For example:

Some questions can be hard to understand because of the complex structure and unfamiliar vocabulary in the sentences.

is easier to understand than

Because of variations in syntactical complexity and esoteric diction, diverse questions may not be uniformly comprehensible.

Simply put, the hardest reading questions on the SAT have both increasingly difficult vocabulary and more complex sentence structure. The lexile score of the SAT is nearly two grade levels higher. The hardest reading questions on the SAT are harder than the hardest reading questions on the ACT.

So, what can you do to be prepared for the challenges brought by the new SAT? Stay tuned for the next blog post about working memory!

The ACT “Enhancements” that were announced last year will begin on a small scale in April and for all students in September. Current juniors in the class of 2026 are already asking themselves, “Should I take the current ACT or the Enhanced ACT?” since they’re in the unique position of being able to choose: they can stick with the current ACT through the spring and summer, or they can start taking the new test in April, knowing it’ll be the same in the fall if they to continue testing to reach their goal scores.

Our best advice for almost all students is to take the current ACT and not the new digital ACT. That’s not surprising, since there’s usually a period of adjustment for any new test while its creators fine tune both the content on the test and the consistency of its delivery. During that time, students have fewer and less accurate practice resources with which to work, and tutors and teachers have less understanding of the test, typically resulting in more variability in scores and more anxious students. In the case of this new ACT, though, particular design choices have been made that render the test even more susceptible to this sort of volatility, so if you’re a high school student or a parent, don’t even consider taking the new ACT until you have to in September.

How are the structure and length of the ACT changing?

The ACT is about to do something it rarely does: change. The new ACT “Enhancements” announced last year represent the greatest changes the test has seen in almost 40 years. While the SAT has existed in no fewer than six different incarnations in that time, the ACT has remained relatively unchanged since the last major revision in 1989. It’s been the same four English, Math, Reading and Science sections ever since. Until now, that is. Going forward the ACT Science section will be optional and no longer a part of the “Core” ACT.

On the one hand, it’s difficult to understand why the ACT would choose now to drop the Science section. We live in an ever increasingly technological society, understanding data and science is necessary to be an informed citizen no matter what path in life you choose, and American students are consistently lagging behind others in tests of science proficiency. On the other hand, it’s crystal clear why the ACT dropped the Science section. Time. Their competitor, the College Board, debuted a newly revised digital SAT last year that checks in at a svelte 2 hours and 14 minutes of tested time, compared to the current ACT’s 3 hours and 20 minutes, if you include the field test items at the end of the exam. Many students and schools have been choosing the SAT simply because it’s the shorter test, and the ACT needed to change to compete.

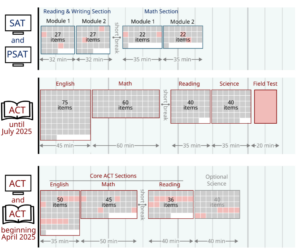

The figure below depicts the structural changes to the test. The Core ACT now consists of 131 items in 2 hours and 5 minutes of tested time. That’s much more in line with the new SAT’s 98 items in 2 hours and 14 minutes and preserves the more speeded nature of the ACT compared to SAT. While many critics have pointed to the length of standardized tests as an unnecessary barrier to student success, and many students will surely welcome a shorter testing experience, that benefit comes at a cost. And the cost is the precision of the test. The SAT recently cut almost an hour from its test, but it did so by transitioning to a computer adaptive test. The difficulty of questions students encounter on the SAT depends on how accurately they’ve answered the questions they’ve already seen. Thus, College Board was able to decrease the total tested time on the SAT while still maintaining its accuracy.

The new ACT, however, will remain a static, linear test. It’s not adaptive and doesn’t change to match students’ ability levels, so the reduced number of questions will necessarily result in more score variability. What’s more, ACT has finally made the responsible decision to incorporate the field test items – questions that are being tested and do NOT contribute to student’s scores – into the test sections themselves so that they can gather more accurate data. The Reading section, for example, now only has 27 scored items and a score scale of 1-36. That’s not a lot of granularity. The ACT knows this and, to its credit, has released the data. The Reliability score of that section has decreased from a 0.89 to a 0.84. That might not seem like much, but – like many test questions – it’s just a math trick. The reliability is on a scale of 0 to 1 and is the opposite of the variance of the test, which has thus gone from 0.11 to 0.16, an almost 50% increase. To students for whom every point matters, that’s quite a jump.

It remains to be seen whether the ACT can deliver on the promise of a shorter, static test that retains its predictive validity. The good news here is that the ACT – unlike the College Board – still plans to continue its Test Information Release program, so we’ll be able to monitor those “curves” on future tests and hope to re-evaluate our opinion.

What ACT content is changing?

In addition to the more obvious large-scale structural changes noted above, updates have also been made to each of the section blueprints – that is, the percentages of different types of problems that make up each section. ACT makes these sorts of pedagogical adjustments every few years, taking into account feedback from stakeholders at both high school and university levels. The changes to each of the sections are noted in the table below.

Content Changes for 2025 ACT

| English | • The section will continue to be passage based, requiring students to incorporate greater context.

• All questions, even grammar questions, will have a question stem.

• Grammar questions will be deemphasized and replaced with questions about the production of writing: its purpose, structure and the author’s goals.

|

| Math | • An effort has been made to reduce the wordiness of the math section.

• The content of the test is on balance the same level of difficulty, yet has changed at the margins: the ACT is deemphasizing both basic skills questions and the most academically advanced content on the test.

|

| Reading | • The reading passages are slightly shorter and feature 9 rather than 10 questions each.

• Test questions will focus less on details and main ideas and more on recognizing arguments and evidence and separating fact from opinion.

• The level of diction and abstraction required from students to understand the passages is expected to increase.

|

| Science | • Passage will have an increased focus on engineering and technology applications in addition to the basic science currently found on the test.

• More background content knowledge may be required to navigate questions on the new, optional Science section.

|

Most of these changes move the test in the right direction. Those wordy, basic skills math questions were always amongst the most poorly performing on the test. And actually requiring science content knowledge on a section entitled “Science” is a good thing. We, of course, lament the loss of grammar on the test. While we understand stakeholders report that students have digital tools and no longer need to know grammar rules themselves, we’d take the ACT’s newfound commitment to honoring digital tools more seriously if they’d integrate a modern calculator into their testing platform! Ultimately, however, it’s too soon to really know how the content changes might compare with those recently made to the SAT last year. It’s likely the case, however, that the stereotypes we know will continue to ring true: the ACT is the more speeded yet straightforward test, and the SAT is the slower-paced, “trickier” test.

How will the ACT be delivered?Will the new ACT be on paper or on a computer?

While the adaptive SAT must be taken on a computer using the College Board BlueBook app, the ACT has pledged to continue to offer the new ACT both in paper and digital formats, a move that’s great for students, who now have a choice as to which format to take. The roll-out of the digital test, however, has not been smooth. Unlike the SAT, which may be taken on personal devices, the digital ACT in its current form must be taken on school managed devices. That’s turned out to be a difficult pill for schools to swallow, leading to fewer test sites for the digital test. For example, the closest digital testing site to the DC Metro area for the April test is in Dallastown, PA, over 60 miles away. But a paper test? Plenty of seats available. Providing proctors for a few hundred test takers on a weekend may be a hassle; scrounging up functional, charged computers for every one of those students is a true challenge. The ACT is piloting a bring-your-own-device program now, which they’ll likely need for the test to be accessible as it has to be for widespread adoption.

If the ACT wants its digital tool to be successful, it also needs to standardize the experience. Right now, there are actually three slightly differing formats depending upon whether a student is taking the school day test, a national test, or an international test. And we’re not just talking about minor formatting issues here – one of those formats has the online calculator Desmos integrated, and the other two do not as of yet.

We applaud ACT’s efforts to maintain a paper test in the face of change, as there are students for whom that’s a definite advantage. But the future of standardized testing is digital, and the future is now. The ACT must update and smooth the digital experience for students if they want to remain competitive.

What will colleges make of the new ACT?

In the past, we’ve consistently overestimated the degree to which college admissions officers interrogate details of a standardized test score report. Now, our best advice is to focus on achieving the highest superscored composite score possible, since that tends to be the number many colleges care about the most. We don’t actually expect many or even any colleges to require the ACT Science section, just like we see very few colleges continuing to require the optional Writing (essay) section. It may be the case that students applying as STEM-focused candidates or to engineering schools may be required to take the Science section, or we may get the dreaded “recommended” rather than required. In the same way, if ACT decides to superscore the new ACT with the old ACT – and they likely will – most colleges will likely respond by entering that superscored number ACT provides into the field for “ACT Score”, just like they have been for years.

Final Thoughts

We haven’t even seen a full-length mock ACT yet, so it’s a little difficult to say much unequivocally about the new test. While there are the bones of a good exam here, the ACT has plenty of work to do before the test gets its full launch in September. The only thing that’s certain at this point is the uncertainty it brings, which is why we’re admonishing all our students to stick with the ACT they – and we – know.

Another Autumn has come and gone and another first marking period is in the grade books. The leaves are falling from the trees and, for some students, the wheels are falling off the bus academically. If that’s the case, not to worry, the school year is still young with plenty of time for improvement. Realizing that improvement, however, takes an understanding of what’s gone wrong. Here are some questions you should consider as you think about how best to help your child.

Is there a learning gap or a testing gap?

If we’re getting a call for academic tutoring help, that often means that grades have already been impacted in some way – ranging from a hiccup of a below-average quiz or test to the more serious problem of a failing report card grade. The disconnect that caused that result, however, can take many forms, so start with the basics: Was the student unable to learn the material or were they unable to display what they’ve learned?

There are many reasons a hard-working and engaged student might feel comfortable with the material in class but have a difficult time with an assessment: Perhaps their teacher writes tricky multiple choice questions they have a hard time disentangling? Maybe they’ve been a little sleep deprived? Or maybe it’s simply the ever-increasing test anxiety and the pressure to get As. Those are all fixable problems, but finding the solution requires first finding the problem.

Perhaps the most serious problem is if the student really is lost and struggling to learn in class. That needs to be addressed immediately, since every minute the student spends in class not learning widens the gap between expectations and understanding, not to mention making them feel their situation more hopeless.

Such disconnects can be the result of a mismatch between the personalities of the teacher and student or between their teaching and learning styles. We help our students begin to take responsibility for their own learning and be able to adapt to those different teaching styles and personalities that they’ll continue to encounter in college and beyond. Perhaps they need to alter the way they take notes or do homework or use the book, but students don’t always know exactly how to make the tweaks that’ll help the most – which brings us to our next question.

Do they have the study skills they need to be successful?

While it’s easy for parents to blame a student’s work ethic and say they’re “not really trying” or “not working very hard”, it might be the case that the student doesn’t know HOW to try harder or work more efficiently. In fact, if you’ve got a freshman or sophomore who’s struggling, it may have more to do with the transition to upper school than the particular class itself.

Many smart students don’t really need to study in middle school: they pay attention, they do their homework, and they do well on the tests, which look very much like the homework. But that natural talent can only carry students so far – at some point they need to learn how to actually study and learn on their own. In high school, the tests won’t always look just like the homework and they’ll need to – gasp! – do some actual thinking on the test. That requires more thorough preparation, since it’s not enough to be able to recall facts; students need to understand relationships well enough to integrate and synthesize on test day. We routinely help guide students through the process of learning how to study: How do they create a study guide? Should they use their textbook? How? And how do they integrate that information with what their teacher is emphasizing in class? How do you outline a paper? Or go from a rough draft to a final edit?